How do you get the book and the reader to the right place at the right time? Strategies have varied over the last few decades, and have resulted in a generalized model for new releases: a first print run that guarantees a presence in the bookstores that are usually attended with a few copies, but not too many, but enough.

Perhaps for a few weeks, until the new novelty service arrives, the book will be patiently awaiting its reader. Perhaps on a novelty table, in a display window, on a shelf. And then? It may be destined for a branch or head office warehouse or return to the publisher’s hands.

The books begin to accumulate. The publisher’s investment is tied up. The author’s impatience increases. The frustration of the reader who does not find his book surfaces. Obsolescence arrives.

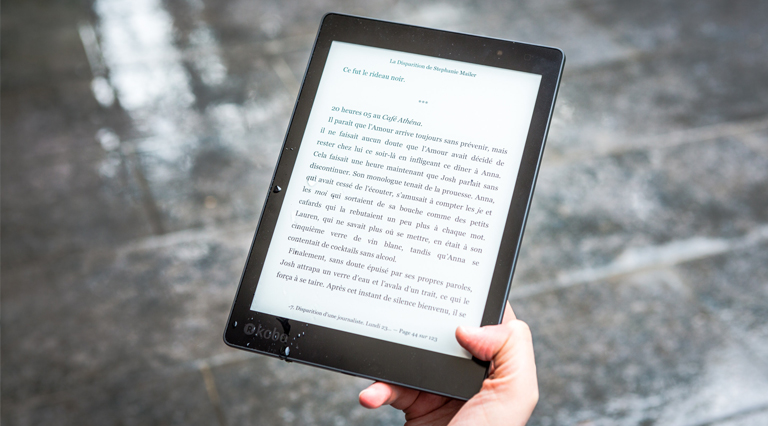

It is possible to find another paradigm, which is not new, but which may have really found its maturity from 2020 onwards. By achieving optimal graphic production times (a maximum average of 72 hours) and efficient logistics, we can choose to have the entire publishing catalog alive and zero physical stock. The key lies in the optimal management of the editorial catalog and its combination with print-on-demand networks: complete and up-to-date metadata will allow the book to meet its reader at the right place, as well as suggesting selections tailored to the reader’s preferences.

Richard Charkin, director of Mensch Publishing, observes: “Waste is endemic in the publishing system. Waste of time, waste of materials, waste of effort. I thought we could eliminate much of this waste through smart, quick decision-making, avoiding redundant stock, avoiding unearned advances and bad debts. To some extent we have succeeded, especially when we have used print-on-demand technology. In this case, books are only supplied when they are sold outright, thus eliminating returns altogether, and there is no need to monitor stock levels or worry about the need for and size of reprints.”

Beginning in 2015, alliances between publishers and graphic workshops in Latin America accelerated. These synergies were consolidated in projects such as Livriz Sell & Print, which integrates and makes 220,000 titles available for the entire region.

John Ingram, president of Ingram Content Group, says: “Print on demand is driving the publishing industry, offering seamless digital and physical distribution of diverse content across different languages and regions. These innovations are spreading around the world to the benefit of the publishing world and consumers.”

Publishers make their titles available. Bookstores and distributors can add them to their offerings. At the reader’s request, the bookstore orders the print copy(s) from its integrated digital catalog provider with print-on-demand. The book arrives at the bookstore in 72 hours. “A virtual warehouse is achieved without maintenance costs and with immediate response 24 hours a day, 365 days a year,” says Damian Cuello, director of Livriz Sell & Print.

The costs of stock maintenance, shipping and returns logistics, losses due to product damage and obsolescence due to stock immobilization are eliminated.

With the conjunction of integrated publishing catalogs available for all marketing channels and print-on-demand, obsolescence has come to an end and the dawn of an efficient and bibliodiverse publishing market.